Last year’s Vermont Water Color Society annual meeting included a demo by artist Sean Dye in which he painted a sunset scene with Holbein’s “Luminous” line of fluorescent watercolors. The colors were mouth-wateringly brilliant, and we all got free samples of the paint! So what’s the story on fluorescent paint? What’s it made out of, and do I want to use it?

We perceive paint colors because the paint absorbs light and then re-emits light from a certain section of the visible spectrum, which we see as its color. Orange paint emits orange light, green paint emits green light, etc. Light from the rest of the spectrum is dissipated as heat. Fluorescent paint is different. It both absorbs and emits light from a wider portion of the spectrum, including ultraviolet light. It’s literally brighter – as in, it emits more light. That’s why fluorescent colors show up even in dim light – and why they shine brightly under an ultraviolet “black light.”

Unlike most paint, Fluorescent paints are made using dye, not pigments. Dyes completely dissolve in water, whereas pigments are insoluble particles. The paint manufacturer Golden says they make their fluorescent paints by dissolving dye into a “transparent solid polymer carrier.” Bruce MacEvoy (of the paint info site, Handprint) says that at Holbein “the dye is formulated by dissolving it in an inert, insoluble resin, then crushing and grinding the cured resin matrix to the desired particle size.” This makes fluorescent paints extremely transparent – something we watercolorists know how to use to advantage (thin washes over white paper!)

With a pigment, only the surface of the pigment particle is exposed to light, which helps prevent them from fading. Dyes, on the other hand, even when mixed with resin or polymer, are much more exposed and fade quickly – I suppose because the carrier is transparent and offers little protection, though I haven’t found exact information on that. In addition, absorbing UV light fades things, and since fluorescent paint absorbs more of it, it fades faster. When I tested some fluorescent dye-based gouache and watercolors by hanging swatches in my window, they were noticeably faded in only a week or two.

This is a deal-breaker for fluorescents as far as I’m concerned. Even if I’m just playing with paint for my personal pleasure, I’d still like to hang the results on the fridge and enjoy them for more than a few weeks – or be able to mail them to a friend without a disclaimer on their longevity. I’m still feeling sad about a beautiful postcard my friend Polya gave me (painted with White Nights watercolor) that faded to pure white in about a year. UV inhibiting varnishes or museum glass, the usual remedy for fugitive paint, don’t work here as they block the UV spectrum light that gives fluorescent paint its extra glow, changing it to just… paint. (On the plus side, this would be a good way to test the UV inhibiting quality of your varnish! Hmmm… I see another blog post on this…)

As a further reason to avoid these paints, many of the dyes used are fairly toxic. Rhodamine dye, used in many fluorescent paints is “toxic and has been banned from use as a food and cosmetic colorant,” according to Kimberly Crick’s research. MSDS sheets list the following hazards: “Risk of serious damage to eyes. Limited evidence of a carcinogenic effect. Harmful in contact with skin and if swallowed. Toxic to aquatic organisms, may cause long-term adverse effects in the aquatic environment.” A Google search of papers on the subject mentioned “liver failure” and “acute poisoning” in instances associated with large doses. Although some other paint pigments present hazards as well, most are not harmful unless ingested or inhaled.

Unfortunately, avoiding fluorescent dye is harder than you’d think. It’s the colorant for many alcohol-based colored markers and brush pens (guess I’ll quit letting my kid draw on herself with Sharpies…) and inexpensive craft paints. It’s also commonly added to gouache paints and even some watercolors (especially violet and hot pink or “opera” colors) to up the brightness. Looking at Violet and Pink options from major paint brands available from Blick and Jerry’s Artarama, Holbein, Shinhan, Mijello Mission Gold, and Turner (all made in Japan or South Korea) had paints made with fluorescents, including colors outside of Holbein’s “luminous” line. According to Kimberly Crick, it isn’t even always listed as an ingredient by some brands. If you want to test for yourself, get yourself a black light and shine it on a paint swatch.

Of course, I did want to test for myself – and I had a blacklight already. (Why? Because Tomato Hornworms fluoresce bright green, which makes them easy and fun to find in the dark.) I didn’t discover any hidden fluorescents in the paint I checked, but some Turner Violet acrylic gouache with dye on the ingredient list lit right up.

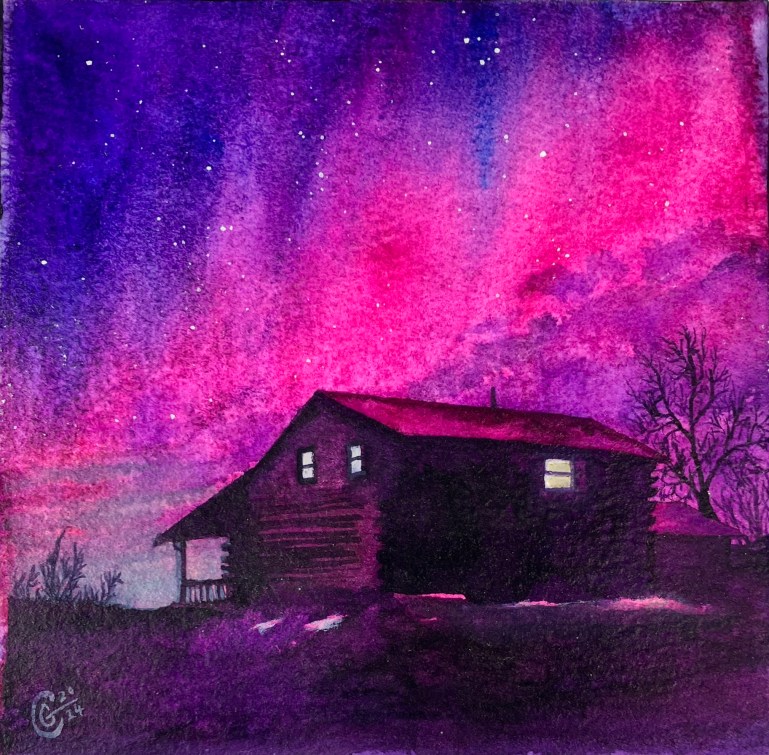

So what’s a hot-pink loving girl to do? I think the answer lies in using the very cleanest, most transparent, modern pigments available. Quinacridone Rose, Phthalo Blue, and Hansa Yellow Light are very bright, and pretty reliably light-fast (here’s a great value set of all three if you need to stock up). Clean (two color only) mixes and transparent washes over bright white (not natural) paper keep them brightest. Placing complimentary colors and dark and light valued colors next to each other also makes colors pop. In the photo below, you can see Quinacridone Rose (PV19) compared to two fluorescent paints of similar hues. It’s not as bright, but it’s close enough that when played up against Indanthrene Blue and Black in my painting of Northern lights it looks pretty luminous.

If you’d like to read more about fluorescent paint and dye, here are some interesting sources I used for this post:

- “Bottling A Shooting Star” – Golden’s “Just Paint” blog

- “Dye Based Art Supplies” – Kimberly Crick

- “Flourescent Color Theory” – Day-Glo Website

Do you use fluorescent paint? Would you want to? Share your thoughts in the chat!